Why did you become a biologist?

When I first entered college, I didn't initially set out to become a biologist. My brother was the first to go to college in my family, and, like him, I originally majored in engineering. This was at a small liberal arts college in northern Indiana (Saint Joseph's) where I also had the opportunity to play collegiate basketball for a couple of years as well. After transferring to IUPUI for my junior year, I refocused my education in biology because it better aligned with my interests. I initially was pre-med, but that segued into a middle school and secondary education certificate in biology/chemistry that coincided with my Bachelors degree in biology. The plan at that time was to teach and coach basketball in my native state of Indiana. However, at IUPUI, you were required to do a research project to graduate. I did mine in a plant cellular and molecular biology lab led by a new professor in the department Dr. Stephen Randall. I was blessed to have Steve as a mentor. It was under his direction that I first experienced basic science research and under his encouragement and guidance that I continued those efforts, eventually getting Masters and Doctoral degrees under his tutelage. Those positive experiences provided the foundation for believing that a career could be made from both education and research. Obviously the cancer-related research I do today seems distant from the work I did as a graduate student studying calcium-binding proteins in plant cell vacuoles, but the focus on membrane protein function, regardless of biological system (plants, yeast, cancer) has been a constant throughout the 24 years I have conducted laboratory research. Other outstanding postdoctoral mentors (Dr. Bill Wickner at Dartmouth and Dr. Sara Courtneidge at the Van Andel Institute, now at the Oregon Health and Science University) further equipped me for the position I hold at App State today. It is here that I hope to provide another generation of students the same exciting research opportunities and experiences that I was provided during my formal education years ago.

Where are you originally from and how did your childhood influence your career decision?

I was born and raised in the small, southern Indiana town of French Lick, probably best known for its sulfur springs and the two large hotels that sprung up from it, as well as for one of basketball's biggest icons in Larry Bird. While neither of my parents or extended family had an education beyond high school, the environment within and around my home encouraged learning. We had a set of World Book Encyclopedias that I thumbed through quite regularly. My mother was an avid reader and a fan of crosswords and other puzzles. And coming from a small and safe small town, I grew up with a lot of freedom to explore my surroundings, so doling off into the woods with friends, visiting the local park to play basketball, or bicycling around the town were common childhood experiences. When combined with my own success as a student, I knew the sciences was where my ultimate calling would reside, though the specifics took a bit longer to evolve.

Who was your inspiration?

I'd say my inspiration has come by committee. My immediate family provided a safe and nurturing childhood free to explore and thrive. My wife, Michelle, and her family have given their continuous support and patience. And I couldn't ask for three better mentors to help me navigate the many steps of my education and training. So lots of folks have inspired me to do and be my best throughout my life. I've truly been blessed in that regard.

If you had to do it again, what would you be?

If I was not to be directly involved in teaching and research, then I think I would pursue a career as a veterinarian. I love dogs, and, though my view of such a career is naïve, it seems like it would be a good way to bring my existing knowledge and passions together in a related, but very different occupation.

What courses do you currently teach? Are you planning to teach any new courses in the near future?

I teach Cell Biology, both lectures and labs and I have recently introduced a Special Topics course entitled Cancer Biology.

What do you like most about teaching?

What do you like most about teaching?

The thing I like most about teaching is the challenge, almost the puzzle, of making complex information accessible to a wide audience. I also enjoy the give-and-take that comes with teaching, the interactions with the students, and the opportunity to help students reach their educational and career goals. Beyond that, there is a hidden benefit to teaching as I naturally gain a greater breadth of knowledge that helps move my own research into areas that may have previously been unappreciated.

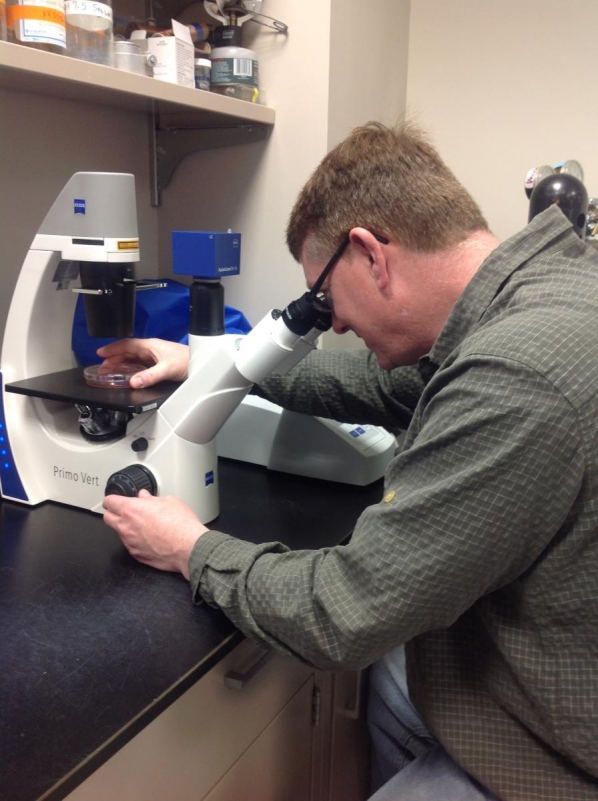

What is the overarching goal of your research program?

My lab studies podosomes and invadopodia, cytoskeletal structures of normal and cancerous cells with an invasive phenotype. In the mid‐1980's, as researchers were just beginning to characterize the cell biology of cancer, there was perhaps no phenotype quite as remarkable as that produced by a cancer-causing gene called Src. Src‐transformed cells had a radically altered cytoskeleton in which the normal linear arrays of filamentous actin known as stress fibers gave way to the punctate actin‐driven cell surface protrusions that could engage and proteolytically modify surrounding tissues. In so doing, Src‐transformed cells could essentially chew their way through the barriers that encapsulate all cells, and in the context of cancer be freed to disseminate to distant sites of the body, thus giving rise to metastatic disease, the leading cause of death among all cancer patients. We analyze these structures through the conduit of a Src tyrosine kinase signaling pathway involving an adaptor protein called Tks5 (pronounced 'ticks-5'). We use cell, molecular, and genetic approaches to elucidate the role Tks5 plays in scaffolding podosome/invadopod machinery. Building these structures and regulating their activity are tightly controlled cellular processes and, notwithstanding the relationship to tumor progression, has far-reaching implications in terms of immunosurveillance, bone remodeling, and the development of blood vessels.

Can you give us a synopsis of your research projects?

In the past, we have studied how Tks5 influences podosome development in macrophages and smooth muscle cells, and these projects continue. Macrophages are of particular interest, not only because of their essential role in innate immunity, but because they often accumulate within the tumor mass. How such tumor-associated macrophages function in cancers of the breast, prostate, and brain (glioblastomas) are also ongoing projects. How Tks5 influences the podosomes of normal cell types and the invadopodia of tumor cells are likely to be complex. Tks5 has multiple, Src-regulated phosphorylation sites that may alter its structure and therefore its scaffolding activity. It has multiple handles in which to associate with other cellular proteins (most of which are uncharacterized) and with the lipids of the cell's membrane. Does Tks5, for example, have different activities based on its location in a cell? And finally Tks5 has several isoforms derived from alternative splicing that each may exhibit unique and differential activities. Working in my lab affords the opportunity to dissect these molecular features of Tks5 in order to broadly appreciate the life of normal cells and its implications for human health and disease when things go awry.

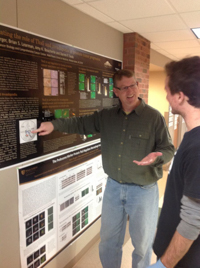

What are you most proud about in terms of the research you've been a part?

I guess I've been proud to find some success in research on several unrelated projects over the years. As a graduate student I was able to publish a couple of papers on calcium-binding proteins in plant cell vacuoles. As a postdoc I published papers on the process of vesicle fusion in yeast. Now for the last 12 years or so, I've worked on Tks5 and podosomes/invadopodia in the context of cancer. I had one paper that made the cover of Cancer Cell and that was very exciting. My mother died of breast cancer while I was in graduate school, and I think it is gratifying to be involved in cancer-related research today. I think she would have been proud of that.

What do you like most about doing research?

I like the process of science. The art of designing good experiments to answer the biological questions my lab is pondering. I also like the aspect of research where previously unknown biological principles are exposed, and that I can be on the front edge of such new discoveries. Research is certainly a challenging enterprise from experimental problem solving to grant writing, but no two days are the same, and when things fall into place (and they do, eventually), the experience pulls you in.

What advice do you have for undergraduates/graduates pursuing degrees in biology these days (or advice on how to be a successful student at App State)?

On a logistical level, my advice to students is to be proactive in their education from the moment they first step on this campus. Students need to explore the breadth of opportunities within their discipline, and directly experience them to the extent possible so that they are better informed of potential career opportunities. They also need to strive to do their very best in their courses. Competition for professional programs and jobs can be fierce. While grades do not necessarily indicate aptitude or success, they are first impressions that can make or break the opportunity to be interviewed. More broadly, I would encourage students to embrace this educational experience that App State provides. There is much to accomplish and contribute with a biology degree, in terms of the environment, in medicine, and/or in all that we understand about the living world. I'd advise students to use these experiences, not only to further their own careers, but also for the broader purpose of making this world a better place to live.